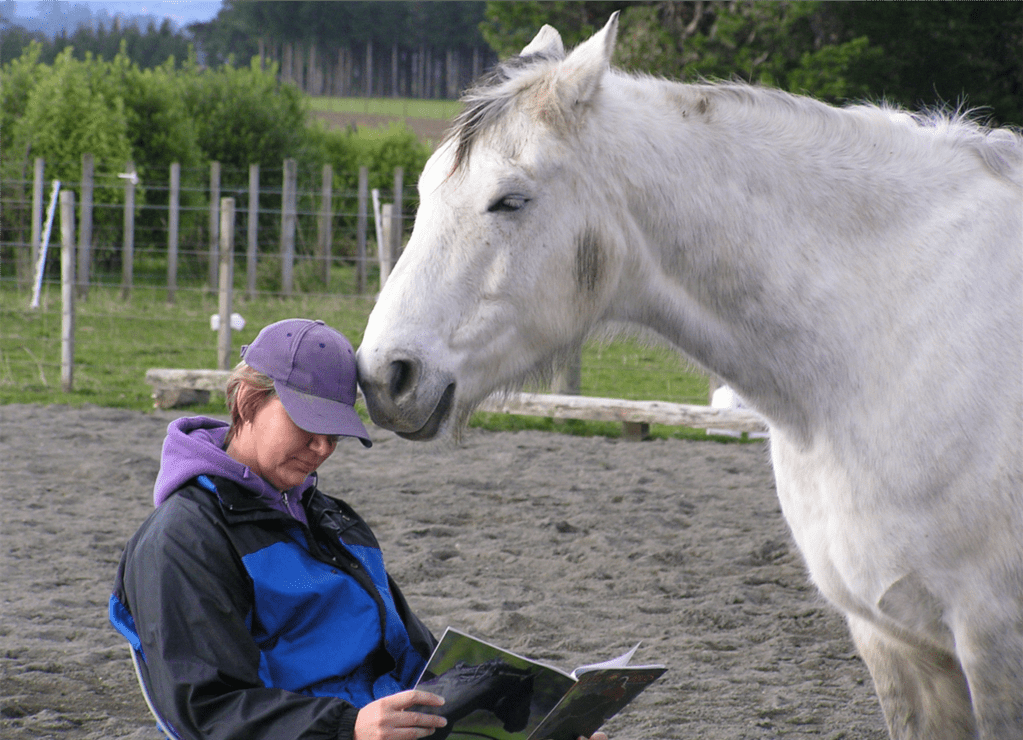

In the photo above, I am starting Boots’ education about LP5 by asking her to walk into a lane to target the yellow barrel. Using a lane ensures that she does not get used to turning toward me when I click while I’m beside her hindquarters. I move forward promptly but quietly to deliver the treat.

Leading Position 5 (LP5) finds us beside the hindquarters. We can be facing the same direction as the horse, facing his hindquarters, or we can be facing backwards (as for hoof care). If we are facing the horse side on, we are in both LP5 and LP8.

Grooming, care of the tail, hind legs and hind feet all require us to be in LP5. It’s also the position vets use to insert a thermometer. LP5 is another intermediate position toward having the horse comfortable with us right behind him in Leading Position 6 as we would use for long reining or driving. We also use LP5 for everyday care like putting covers on and off, as well as harnessing and unharnessing if we drive our horse.

Tending hind legs, feet and tail require the horse to be confident with us in that position.

Walking beside the hindquarters builds the horse’s confidence about having us remain well behind his drive line as we walk along, as well as responding to our go and whoa signals while he is walking with most of his body ahead of us.

Walking out and about on the road in LP 5 is a great exercise to prepare for riding, long-reining or driving.

If the horse shows anxiety or unease when we are by his hindquarters, he is giving us important feedback.

It means we have to write a thin-sliced Individual Training Program to address what the horse is telling us about his comfort zones. For information about the ART of thin-slicing, see Number 13 in my Blog Contents Quick Links at the top of the page. Also, for much more detail, see my book, How to Create Good Horse Training Plans (link to my books is also at the top of the page). Information about comfort zones is at Number 107 in my Blog Contents Quick Links.

It’s definitely worthwhile to spend time and effort to have our horse confident about our presence alongside his hindquarters. We also need him to be sensitive to any signal we may give to ask him to halt, move forward, and eventually to yield his hindquarters or bring his hind end toward us.

Training Plan

Aim

To have the horse confident when we move from LP4 into LP5 while he is walking along.

Environment

- Horse in an area where he is usually relaxed and confident.

- Herd buddies not able to interfere but in view if possible.

- Horse in a learning frame of mind.

- Body extension to clarify signals as necessary to send energy toward the horse’s front end to inhibit turning to face the handler, but use it only to clarify your intent. Otherwise it is in neutral by your side.

- Halter and lead. As lightweight a lead as possible. It’s important to keep a drape or ‘smile’ in the rope at all times, so we are not giving the horse ‘please turn toward me’ signals without realizing it.

- During the teaching phase, destinations such as treats in a series of buckets, or mats which the horse knows as targets where he will get a click&treat, will give this exercise meaning for the horse and create willingness to move forward at your suggestion without turning toward you.

- The ideal way to begin this exercise is to create a lane with a low barrier so the barrier doesn’t get in the way of the lead rope (horse in the lane, handler on the outside).

- And later, a safe straight fence or a roomy round pen (walking around the outside or the inside).

- As you move further back, it helps if the horse confidently and reliably responds to a voice ‘halt/whoa’ signal. Practice ‘walk on’ and ‘halt’ in LP3, using rope texting for the halt as necessary, until a voice signal for the halt/whoa reliably replaces the need for jiggling the rope. As the horse halts, quickly but smoothly glide to his head to deliver the treat. You want his head to stay straight. (See Number 16 in my Blog Contents Quick Links for smooth walk and and halt in LP3 (alongside neck/shoulder).

Once Boots understood how to respond to my walk-on and halt signals from LP5, it was easy to send her ahead of me through a curtain for Horse Agility.

Slices

- Begin by walking with the horse in LP3 (beside neck/shoulder). Use a lane to keep the horse straight (i.e. not turning to face the handler) for the initial teaching. The handler walks on the outside of the lane. use destination mats or nose targets to help the horse focus and move forward without wanting to turn toward you.

- After reaching each destination, work out a way to smoothly change direction so you pass through the lane on the horse’s other side next time through. As always, we want the horse equally confident whether we are on his left side or his right side.

- For all of these slices, if the horse wants to turn toward you, disturb the air with your body extension to inhibit that choice. The instant he turns his nose forward again, click, put the body extension into neutral and quickly move to his head to deliver the treat.

- The key is to reward the horse for continuing to face forward. Having pre-set destinations is the easiest way to inspire the horse to stay straight as we position ourselves further and further back.

- Gradually drift back until you are walking in LP4 (behind withers) toward a pre-set destination. As the horse approaches each destination with the intention of stopping there, use your voice, breathing and body language ‘halt’ (drop into your hips plus big breath out) signals; relax (click&treat) as soon as the horse stops. Quickly glide to his head to deliver the treat. We dont’ want him to turn toward you.

- It’s important to keep a drape or ‘smile’ in the rope at all times. Some horses are extremely tuned in to rope signals on the halter and will read any tension in the rope as a signal that you want them to turn toward you.

- When 5 above is smooth and reliable,, add in a HALT before reaching your destination point. That is, ask for a halt in the middle of the lane; (click&treat – move promptly to his head to deliver the treat), then walk on to the pre-set destination. At first you may need to wiggle the rope to support your body, breathing and voice ‘halt’ signal. We want the horse to halt on our voice signal at any time, and stay straight to earn his click&treat.

- Start in LP3 again, drift back into LP4, then drift a bit further back into LP5 and walk on to your destination, staying in LP5. Relax (click&treat) at the destination.

- After treat delivery, move into LP4 (behind the withers) and ask the horse to ‘walk on’ from LP4 adding a light tapping signal with your fingers just behind the withers.

- As 9 above, but now ask for a halt (while you are in LP5) halfway through the lane; relax (click&treat – moving promptly to his head to deliver the treat). Then slip back into LP4 and tap behind the withers as a signal to ‘walk on’ to your set destination.

- When 10 above is ho-hum moving through both directions in the lane, have both of you walk on the outside of the lane, with the lane barrier on the far side of the horse. Use the same destinations, so you have only changed one parameter. (Lots about Parameters in Number 8 of the Blog Contents Quick links.)

- When 11 above is ho-hum, take away the lane and work along the fence.

- Put your destinations further and further apart as the horse gains confidence. Ask for halts between your destinations. Every time you halt, be sure to move quickly to the horse’s head after the click in order to deliver the treat. It’s much easier to prevent turning than to try to stop the turning if he has formed a ‘turning’ habit. Then glide back into LP4 to give the ‘walk on’ signal then glide into position beside his hindquarters.

- Work toward being able to use voice, body language and breath energy signals for the ‘walk on’ and the ‘halt’. Unless it is very windy or noisy, your horse will be able to hear you breathing in or out deeply. He can also see and feel your energy rising or dropping as you make yourself larger (for walk on) or smaller when you drop into your hips (for halt) in LP4 alongside his ribs. (See number 16 in my Blog Contents Quick Links for detail about this.)

- At some point, you will be ready to ask for the ‘walk on’ from LP5, beside his butt. If you used a tap behind the withers to ask for ‘walk on’, the horse will readily learn to understand a tap on his butt as a ‘walk on’ signal. You may want to return to using the lane to teach the tap on the butt as a ‘walk on’ signal.

- It is also helpful, once LP 5 is solid, to teach a clear signal for when you do want him to turn and come toward you. We want the horse to understand that sometimes we ask him to turn and come, other times we simply want him to ‘walk on’ while we walk with him beside his butt. However, teach that lesson well away from the venue where you are teaching and refining this lesson.

Generalization

Play with moving through Leading Positions 1 to 5, first with the horse between you and a safe fence When that is good, we can progress to open spaces. Gradually add more ‘halts’ between the pre-set destinations as your ‘whoa’ gets well established. I.e. Repeat in the open space just what you did in the lane and along the fence. Use destinations to start with. If you have progressed to the road or paddock, it can work to toss a frisbee out ahead as a destination: click&treat when he targets the frisbee. If you’ve taught him to ‘fetch’, he may pick it up for you!

- Start in LP1 (in front facing same way as horse).

- Move into LP2 (just in front of horse’s nose in a parallel track).

- Step back into LP3 (beside his neck/shoulder).

- Drift back into LP4 (behind his withers).

- Glide back into LP5 (beside his butt).

Then do it in reverse order, ie. drift forward through the positions. Relax (click&treat) for good effort. Keep a body extension with you to quietly inhibit any attempt to turn toward you, in case the horse ‘forgets’. Remember to occasionally relax (click&treat) when the horse is moving along staying straight.

We want to let him know, via click&treat, when he is in the action of being correct, rather than after a correction. At this point, I generally build in a voice signal for ‘straight’ when I want him to stay straight. It is handy later when I teach voice signals for right and left turns.

Be careful not to give halter touch signals with the rope without being aware of it. Use the lightest rope or web lunge line that you have available, or can make with cord from the hardware store.

If the horse is totally relaxed with us walking beside his hindquarters, teaching long-reining or ‘guiding from behind’ will probably proceed smoothly.

The video that follows is the same one as in the December blog for Leading Position 4, as the only difference is that we gradually move back so we are beside the hindquarters rather than beside the ribs.