I’m going to focus on Leading Position 7 next because Leading Positions 1 and 2 require us to be in front of the horse, facing away from him.

Leading Position 7 (LP7) has the handler face to face with the horse, either directly in front or a bit to the right or left of the horse’s head.

Remember that horses have a blind spot right in front of them for about 3 feet or a meter, due to the way their eyes are positioned at the side of the head. You can check this out for yourself by cupping your hands in around and in front of your nose to imitate a horse’s long nose. You will notice that you can no longer see right in front of yourself.

In order to feel safe in front of the horse facing away, we want to know that the horse backs up easily whenever we ask him to do so.

Face to face interactions include:

- Greeting (horseman’s handshake).

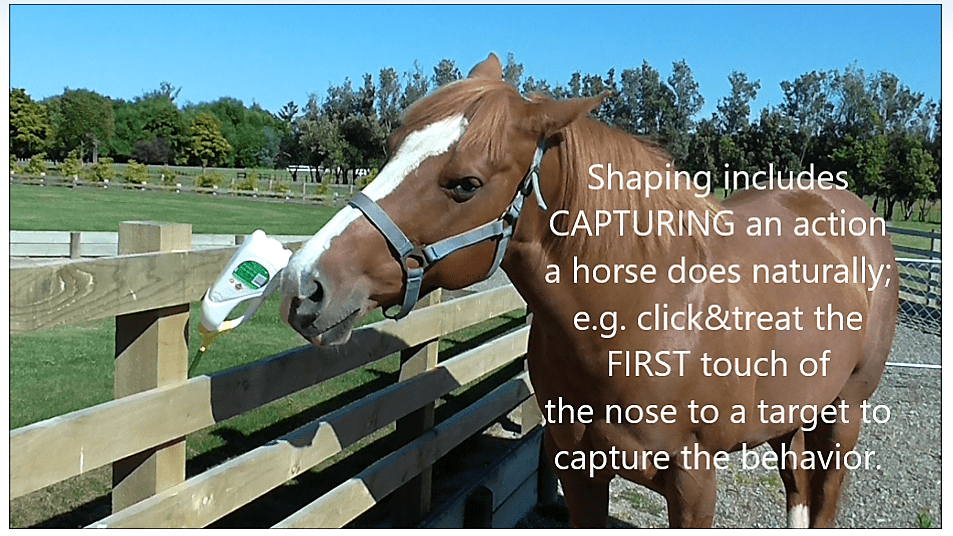

- Teaching the horse to put his nose on a hand-held target often has us standing facing. him, maybe at a bit of an angle.

- Recall, e.g., asking the horse to come to us from the paddock.

- Recall across unusual surfaces, and in a variety of other situations.

- Rope Relaxation: tossing the rope around the horse’s head left to right and right to left.

- Asking for back-up.

- Protecting our personal space bubble while sharing time and space.

- Backing up over a rail and recall over a rail.

- Teaching sideways with the mirroring technique which can grow into a ‘square dance’ when it is paired with back-up and recall.

- Teaching poll relaxation and flexion.

- Tummy crunches

Greeting

When horses approach each other front-on, they usually greet by sniffing noses. If they don’t know each other, a sparring match might follow. If there is a sparring match, typically, one horse will strike out with a front leg. The other horse then retaliates or backs away.

Eventually one will capitulate and move out of range of the other. They may play a chasing game. Or they might both tire of the game and go back to eating or snoozing.

Two horses carefully checking each other out.

So it appears that a face-on approach from the front can be recognized as a greeting or a challenge/confrontation. If the horses belong to the same ‘in-group’, the approach from the front is usually a friendly greeting showing recognition. It resembles the smile and nod we exchange with colleagues at work.

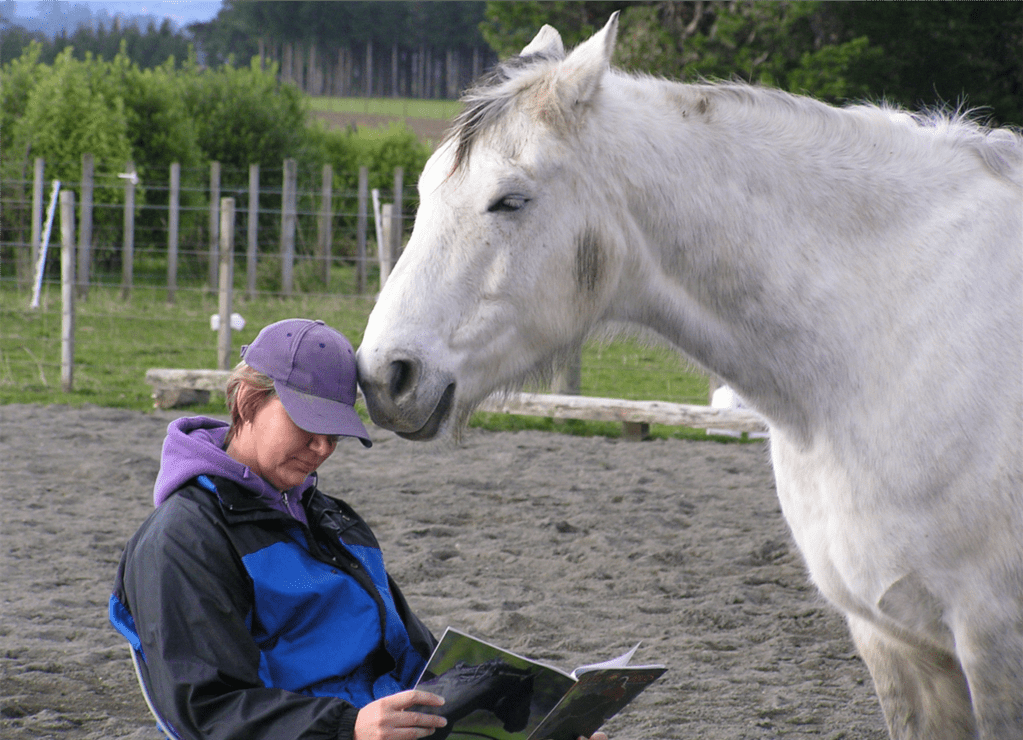

Once we have established a positive relationship with our horse, we can maintain the bond by offering the standard ‘Greeting’ every time we approach. We extend the back of our hand – which stands in for another horse’s nose. We allow the horse to close the last inch of the gap to touch our hand, then we carry on with our business, as would another horse in the herd.

We must let the horse close the final gap between his nose and the back of our hand.

If the horse is not interested in closing the gap to touch our hand, we have powerful feedback. For some reason, at that moment, the horse is not in the mood to greet us. The horse has spoken, but are we listening? We have an opportunity to reflect on why this might be.

We want to develop this into a habit for each time we visit with the horse. To teach the horse, we use the Greet & Go procedure. This seems deceptively simple, but it is extremely powerful to both establish and maintain the connection between the horse and the person.

Generally, horses are not comfortable with having people’s hands all over their faces to ‘say hello’. Horses don’t go around patting each other on the head. Getting people to stop doing this is quite a challenge.

This desire that people have to rub on a horsse’s face is a factor in the biting urge that some horses exhibit around people.

This is sometimes called “The Horseman’s Handshake”. As soon as Boots touched the back of Ada’s hand, Ada walked away. She is using the “Greet and Go” procedure. A greeting like this is the polite way to approach any horse. Once the “Greet and Go” procedure is well established, we can “Greet”, then carry on with what we plan to do with the horse.

Targeting: Teaching the horse to put his nose on a hand-held target often has us standing facing him, maybe at a bit of an angle.

We need to remember that horses have a blind spot right in front of them for about 3 feet or a meter, due to the way their eyes are positioned at the side of the head.

Teaching Back-Up Signals

Straight body with raised fingers tapping the air, plus a voice signal are our cues for backing up while in front of the horse. Here we are working on a straight back-up between two rails.

The following four short video clips show the many ways we can play with Leading Position 7. Be aware that sometimes I use a body extension to help amplify my signal to make it clearer for the horse. Once the horseunderstands what I am asking, the body extension is no longer needed. Eventually we can do most things at liberty with gesture and voice cues.

The body extension is never a ‘punishment’. It merely makes it easier for the horse to understand what behaviour will both remove the signal presssure (negative reinforcement) and earn the click&treat (positive reinforcement). It’s easy to use both methods of reinforcement at the same time. For some tasks, it makes out intention much clearer for the horse. Horses thrive an clarity. I know some people in the clicker training world find this highly problematic, but it doesn’t need to be. It depends on how much finesse, and how many different moves, we want to build into our training program.

Recall

Once the horse knows that a ‘recall’ signal (my rounded open arm position, leaning forward slightly, and voice cue) will result in a treat, we can practice from further and further away. For paddock recall, I use a whistle and reward the coming with an ample treat.

Boots likes to show off her ‘bow’ because she knows it always results in a treat .

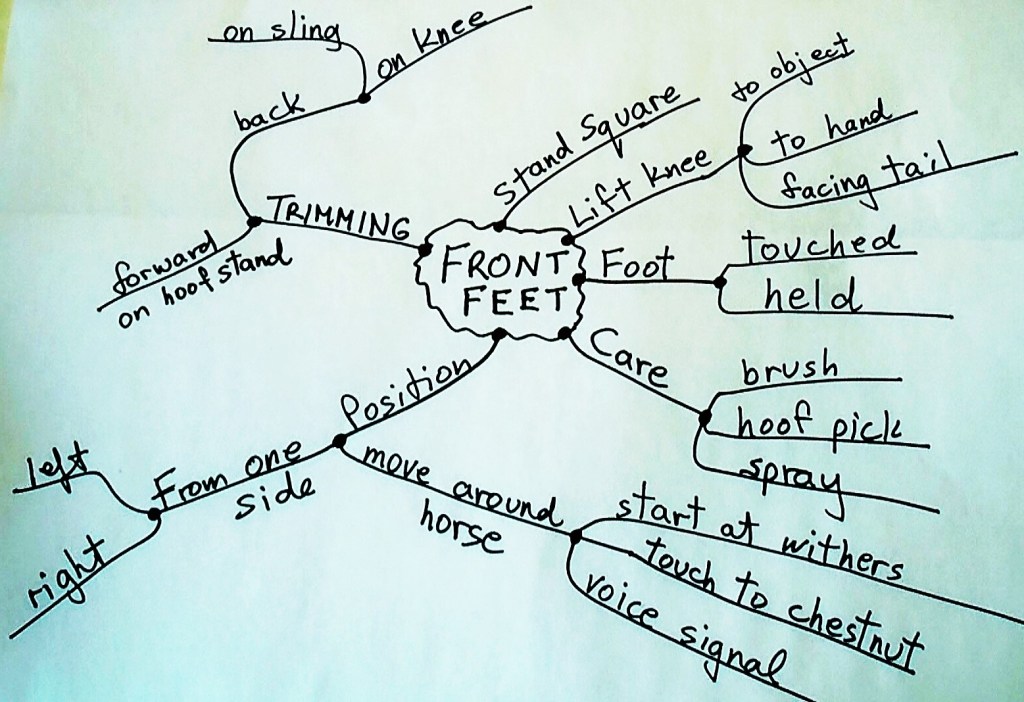

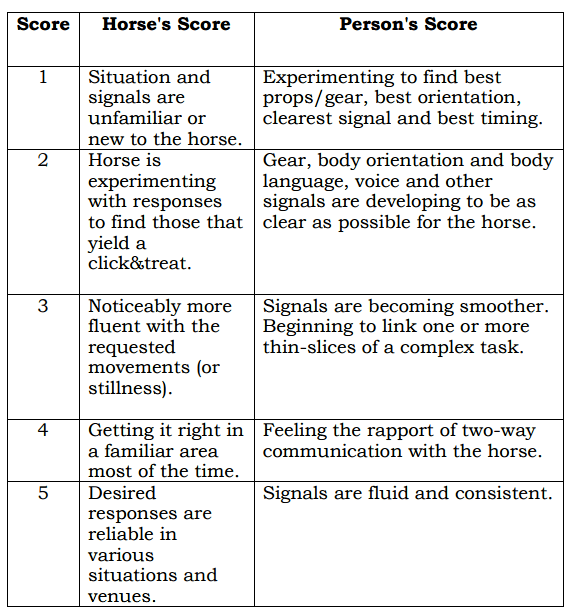

Be sure to check out my blog number 13 (see the ‘Blog Contents Quick Links’ at the top of the page) for using thin-slicing to plan a Training Program. Each task or move you want to teach your horse needs careful consideration of how you will make it easy for the horse to understand what you want – you need to design a Training Plan for each task.

I’d love to hear which move you have chosen and how it is going.